How is the shutdown affecting learning? We talked to local teachers to find out.

Teachers, administrators, and students of all ages across the country have now settled into the “new normal” of schooling amid a pandemic — and at this point, it appears there will be no return to brick-and-mortar schooling for the 2019-20 school year. The current distance learning order runs through the month of April, but both Rochester Public Schools Superintendent Michael Munoz and Gov. Tim Walz have said it is likely distance learning will remain in effect, in Rochester and statewide, through the rest of the school year. In the interim, the district continues to provide meals and child care for families who need it, while classes shift away from physical classrooms to Google and other digital learning tools.

We wanted to check in with teachers and administrators in Rochester Public Schools to understand the various ways their jobs have changed since the onset of the pandemic, what they’ll take away from the experience, and what the public should know about the current education situation. Here are a few snippets of what we learned.

Being home does not make things easier.

Michael Olson, a 5th grade teacher at Folwell Elementary School in Rochester, says distance learning is going well, all things considered. His class of 28 kids hop on a group call for 2-3 hours each day. That may sound like a vacation for Olson, but he says kids tasked with supervising siblings in the daytime may not be able to start school work until after the parents get home. The combination of setbacks and breakthroughs make Olson’s distance learning experience a mixed bag.

“There are new challenges every day,” says Olson. “There are awesome moments. We had a Scattergories game yesterday afternoon … and then there are challenging moments where a student is struggling to understand the curriculum and we are struggling to connect.”

Technology has been a saving grace.

Heather Nessler, director of communications, marketing and technology for Rochester Public Schools, says the extra week added on to spring break gave the district time to figure out its technological response to distance learning. She says the district is “very close” to providing a device for every student who otherwise would not be able to access the internet.

“If there are students sharing a device, let us know so we can try and get them devices,” said Nessler. WiFi hotspots are also available at the 22 different RPS meal service locations.

In addition to the daily online lessons, Olson has instituted a “social hour,” where students get on Google Hangouts and do just that: hang out. (Olson says he monitors the call from a distance, to ensure kids are safe but free to interact how they please.)

“Technology has really helped, for my students in particular,” said Olson.

...but it doesn’t replace in-person learning.

Teachers have made distance learning work, but it is still not the ideal scenario. Heather Lyke, an English teacher at Mayo High School with 160 students spread out over several classes, says software glitches have periodically made it difficult for students to participate.

“For some kids, that little glitch is all it takes for them to disconnect, so you have to work through it as quickly and smoothly as you can,” Lyke said.

“There is learning taking place and we are benefiting from this,” added Olson, “but I won’t say at-home learning is better than in-person learning.”

‘Distance learning’ is different from online learning.

Olson’s lesson plans include daily slideshows, fun and instructional videos (some he records himself), using assignments via Google Classroom, and answering regular questions from students. The school day doesn’t end after that, though; this only takes up 2-3 hours of the day.

In one recent assignment, Olson’s students were assigned to make ‘oobleck,’ a combination of cornstarch and water that has properties of a solid and a liquid. Students were asked to make it, play around with it, and send in videos of the process. It’s part of an effort to make sure kids aren’t simply staring at a screen all day, even for educational purposes.

“They are engaging online, but the one thing I am working really hard to do is not make this online learning. It’s at-home learning,” said Olson. “So, the goal is to not have them sit and stare at an iPad for four hours a day either.”

Distance learning will stick around in some ways.

Even when the pandemic abates, some of the lessons learned by the district in this time will influence how students learn lessons of their own in the future. Heather Willman, a principal on special assignment now focusing on secondary education, says the new rules of engagement have forced the district to prioritize the most important skills from a certain course. In some cases, the simplification may help students become more engaged.

“We are trying to focus on those deep, high-leverage skills, and not worry so much about being able to do all of the mini-kinds of assignments,” Willman said. “Some of those lessons are going to last further than this distance learning period. Because I think it’s really helping us think about what’s most important, and what motivates students and keeps them going.”

Students are asking new questions.

Lyke sets aside about two hours each day to talk one-on-one with her students about anything they may need, whether it be help with homework, direct feedback on an assignment, or general advice and guidance. Increasingly, Lyke says she’s been giving out the latter.

“My sessions have become kids asking for tips on things like making a schedule, using a calendar, or how do you manage your time when it’s not being managed for you on a bell schedule?”, said Lyke. “We have talked about things like creating a place in your kitchen to study so you are not studying in the same place you sleep... just small things like that sometimes as adults we take for granted as something we know how to do — those life skills — and weaving them into the classroom.”

Some teachers may have seen their students for the final time.

Both Olson and Lyke operate at the “finish line” of their respective schools: Olson’s students move on to middle school after they finish in his classroom, and Lyke’s seniors hit the real world, off to whatever occupation they choose. Normally, they are sent off with some sort of celebration: graduation for the high schoolers, a party of some sort for the 5th graders (and, increasingly, they get a graduation of their own, too).

This year, however, those celebrations will most likely have to remain virtual — so it’s possible these teachers have seen some of their students for the last time. Not only does that realization weigh heavily on the students, but the teachers as well.

“With seniors, that’s extra hard because if we don’t get to pull ourselves back together, many are going off to the military, or college, and their roles in the world,” said Lyke. “And so, we might not see them again… that’s hard. And I know how hard that is for me as an adult to say, and so it’s extra hard for kids.”

Distance learning looks different for different age groups.

It’s easy to spot the difference between an elementary school classroom and a high school classroom within a few seconds of walking through the door. Willman said distance learning is no different. Younger kids were sent more hands-on, special equipment via delivery, while students in middle and high school focus more on the virtual side of distance learning.

It’s part of a tailored approach for each age group, to mimic the actual classroom as best as possible.

“With elementary, we had to think a little bit differently about providing things to send home to students,” said Willman. “We are trying to make sure we are responsive to the needs and the ages of the kids.”

...but regardless of age group, teachers realize the challenges still ahead. Distance learning has been hard on everyone.

Lyke admits scheduling has become a problem. Some of her older students are working at grocery stores and senior living centers, which raises a difficult question: when a student is named an essential worker, what title takes precedence over the other? In a struggling economy, the answer isn’t as clear cut for some families.

“That’s the hardest thing — working around 160 schedules and 160 different technologies,” said Lyke. “A lot of our kids also have jobs, and that’s tricky, especially for kids whose parents have been furloughed; a lot of them have been working extra hours to try to help make ends meet at home.”

The new circumstances have also hit Olson, who enjoys introducing collaborative projects to the class and building a sense of community inside his walls. Without a physical space to interact in, that task becomes a little bit harder.

“Everything I feel passionate about in education just got ripped from me a little bit,” said Olson. “But there is still no other job I would rather be doing right now than figuring this out, teaching kids and connecting with kids.”

Report by Isaac Jahns and Sean Baker

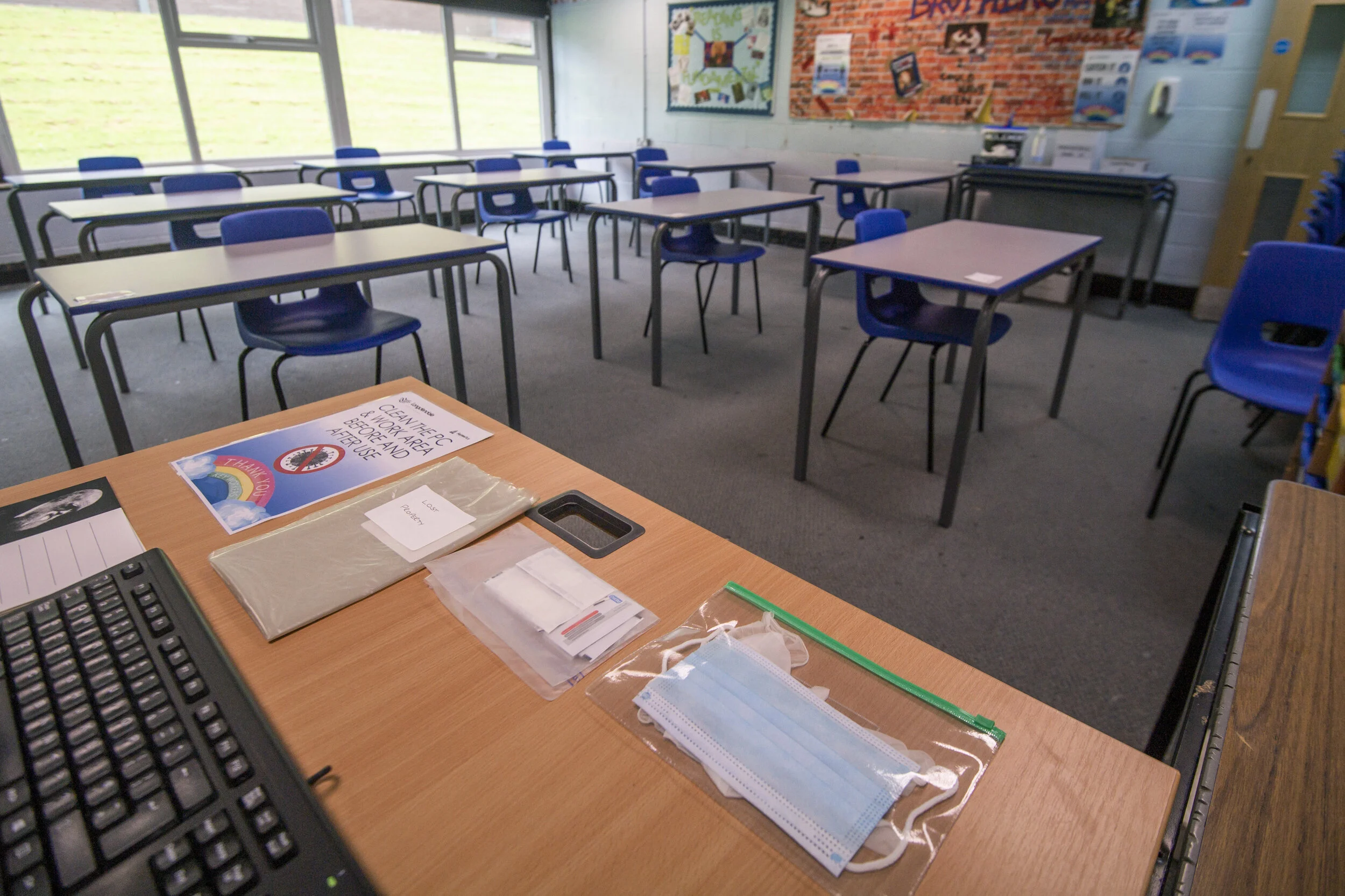

Cover photo contributed by Michael Olson